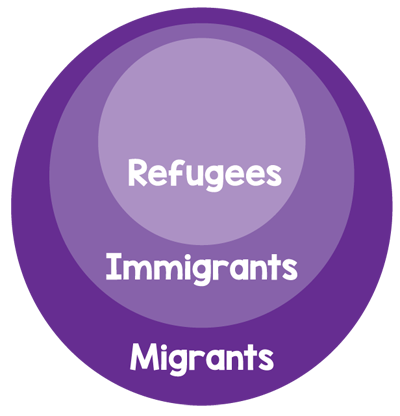

WE’VE ALL HEARD STORIES about refugees and immigrants coming to the U.S. to start a new life. Have you ever wondered what it would be like to leave the place where you grew up and start over in a foreign country? Maybe you have friends whose families immigrated to the U.S. or you even came to New Orleans from someplace else? The New Orleans metro area is home to many immigrants from a lot of different countries, but most are from Honduras, Vietnam, Mexico, Nicaragua, and India.

We wanted to learn more about what it means to be a young female immigrant in New Orleans. Lusher Charter School student Keira “Brooklyn” Armstrong (11) sat down with Mayte Velásquez Pineda (18), who came to New Orleans from Honduras when she was about Brooklyn’s age, to learn more about Mayte’s journey and life as part of the New Orleans community.

Mayte was five when her father immigrated to the U.S. for better job opportunities and to support his family back in Honduras. When Mayte was 12 years old, she left her home to join her father. Together with a group of strangers, Mayte traveled through Guatemala and Mexico and eventually crossed the Rio Grande to reach Texas. Tis trip took one week, but she was caught at the border and spent three weeks in a shelter waiting to be reunited with her dad after seven years of living worlds apart.